Introduction

Imagine you’re developing a video game where the player has to find magical items, build a weapon, and then attack monsters. This would be relatively straight-forward to create. Just throw some magical items around the map, let the player move around to discover them, and leave it to the player to figure out what combination to put together to build a powerful weapon. Easy.

But, what about the NPC? Once we throw a computer-controlled player into the mix, things get a little complicated. How would you tell the computer which items to collect? Should it just move randomly around, pick up random items that it happens to come across, and build whatever weapon that happens to make? It certainly wouldn’t make the most challenging of NPC characters.

There is a more intelligent approach. Through the use of artificial intelligence planning, you can program the computer to formulate a plan. For “easy” difficulty, the computer could have the goal of building a club. For “hard”, the computer could build a bazooka. But, how do we give the computer this kind of planning intelligence?

In this tutorial, we’ll learn about STRIPS artificial intelligence AI planning. We’ll cover how to create a world domain and various problem sets, to provide the computer with the intelligence it needs to make a plan and execute it, effectively providing a much better gaming experience.

What is STRIPS?

The Standford Research Institute Problem Solver (STRIPS) is an automated planning technique that works by executing a domain and problem to find a goal. With STRIPS, you first describe the world. You do this by providing objects, actions, preconditions, and effects. These are all the types of things you can do in the game world.

Once the world is described, you then provide a problem set. A problem consists of an initial state and a goal condition. STRIPS can then search all possible states, starting from the initial one, executing various actions, until it reaches the goal.

A common language for writing STRIPS domain and problem sets is the Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL). PDDL lets you write most of the code with English words, so that it can be clearly read and (hopefully) well understood. It’s a relatively easy approach to writing simple AI planning problems.

What can STRIPS do?

A lot of different problems can be solved using STRIPS and PDDL. As long as the world domain and problem can be described with a finite set of actions, preconditions, and effects, you can write a PDDL domain and problem to solve it.

For example, stacking blocks, Rubik’s cube, navigating a robot in Shakey’s World, Starcraft build orders, and a lot more, can be described using STRIPS and PDDL.

Creating a Domain

Let’s start with the example game that we began to describe above. Suppose our world is filled with ogres, trolls, dragons, and magic! Various elements are scattered in caves. Mixing them together creates new magic spells for the player. Let’s see how we can describe this problem in PDDL for an artificial intelligence planning implementation.

We’ll start by defining the domain. All PDDL programs begin with a skeleton layout, as follows:

1 | (define (domain magic-world) |

That’s it. So far, pretty easy. Let’s add a description of the different kinds of “things” in our world.

1 | (define (domain magic-world) |

What we’ve defined in the above PDDL code is five types of things for our domain. We’ll have players and locations, obviously. A player is the user or computer-controlled character. A location is a specific place on the map, such as an area, country, or region. We’ll use this to separate our map into specific regions.

We’ve also defined a “monster” type, which will describe enemies that might be guarding treasure or a region. Also, an “element” type. This will be our ingredient type for making magic spells! Finally, a “chest” type. This is basically a treasure chest that our ingredients will sit inside.

So, the idea is that the player or NPC must visit different areas of the world, find treasure chests, defeat any monsters guarding them, open the treasure chests, collect ingredients, mix them together, build a powerful weapon, then attack the other players. Whew, that sure is a lot! Good thing we have artificial intelligence planning to help us.

Creating Domain Actions

Let’s define a simple action for our domain. We’ll create a “move” action that allows the player to move from one location to another, as long as they border each other.

1 | (define (domain magic-world) |

An action is defined by using the :action command. You then specify any parameters used in the action, which in our case, we’ll need to specify a player and two locations (the current location and the new location). We then specify a precondition. This sets the rules for when this action is valid, given the parameters. For example, we’ll only allow moving to a new location if it borders the player’s current location. Otherwise, it’s too far away. We’ll also only allow moving to a location that is not currently guarded by a monster. If it is, the player will have to attack the monster first.

Preconditions are specified by using simple logical phrases. The phrase “and (at ?p ?l1)” simply means that the player must currently be at location 1. The phrase “border ?l1 ?l2” means that the two locations must border each other. Likewise “not (guarded ?l2)” means that the second location has to be free and clear of monsters.

Let’s Move Around in the World

Now that we have a simple STRIPS PDDL artificial intelligence planning domain, we can test it out with a simple AI planning problem. First, let’s describe our world with a basic problem and ask the AI to figure out the steps to move the player from a starting location to a goal location.

Creating a STRIPS Problem

1 | (define (problem move-to-castle) |

The above STRIPS AI planning problem, uses the domain that we’ve designed above (containing a “move” action command) to define our world. We’re simply included an NPC and three locations. There is a town where the NPC starts. There is also a field and a castle. The goal, defined by the “:goal” directive, is to have the NPC move to the castle. Seems easy enough.

Solution to the Move-to-Castle Problem

If we run the artificial intelligence AI planning technique STRIPS on the domain and problem above, we get the following solution:

1 | Solution found in 2 steps! |

This is exactly correct - and optimal too! It only takes 2 steps to move from the town to the neighboring field, and finally to the neighboring castle.

Let’s take a look at a slightly more tricky example. We’ll throw a monster onto the field, blocking that path. Instead we’ll provide a different way to the castle and see if the AI planning algorithm can figure it out.

Bypassing the Dragon in the Field

1 | (define (problem sneak-past-dragon-to-castle) |

Notice that this newly defined STRIPS PDDL problem looks very similar to our first one. The difference here is that we’ve defined a dragon and placed him on the field. Since the field is guarded by a dragon (monster), and our “move” action has a precondition that a location can not be guarded by a monster, we can no longer move directly from the town, to the field, and finally to the castle. Our path to the field is effectively blocked. Especially, since we don’t have an attack action defined! The AI must find another way around.

We’ve actually provided an alternate means to get to the castle, by going through the tunnel in town, across the river, and finally to the castle.

Solution to the Sneak-Past-Dragon-to-Castle Problem

If we run the problem, the artificial intelligence AI planner finds the following solution.

1 | Solution found in 3 steps! |

In just 3 steps, the AI can move from the town to the castle, safely bypassing the dragon. What’s even more interesting, is taking a look at the search process that the AI planning algorithm used to find the solution.

1 | Using breadth-first-search. |

As part of the search process, the STRIPS AI planner begins searching at the initial state defined in the problem (player at town). This corresponds to a depth of 0 in the search tree. The AI then proceeds down the child states in the graph of available actions. Somewhere at depth 1, the AI runs into the dragon in the field. At this point, it can not go any further and backtracks to a different branch in the search tree of available actions. It then finds another path at depth 1, using the tunnel instead. Finally, it searches forward at depth 2, finding the river, followed by the castle.

Methods for Searching for Solutions

In the above two examples, we’ve seen how the AI searches through the list of available actions at each state, in order to reach the goal state. But, how exactly does the AI search?

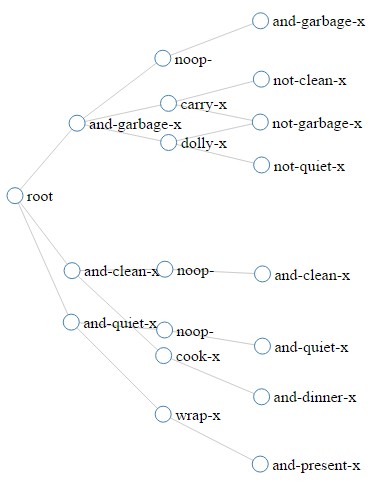

With STRIPS AI planning, a graph can be constructed that contains all available states and the actions that bring you to each state. This is called a planning graph. Here’s an example of what a planning graph might look like (this comes from the birthday dinner domain and problem):

As with most trees and graphs, we can traverse them using a variety of algorithms. For STRIPS artificial intelligence planners, a common method is to use breadth-first-search, depth-first-search, and the most intelligent approach - A* search.

Breadth First Search

Breadth-first-search finds the most optimal solution to a STRIPS problem. It searches from the initial state, and evaluates all child states that are available from valid actions at the initial state. It only evaluates at the current depth, completely checking all states before moving to the next depth level. In this manner, if any of the child states results in the goal state, it can stop searching right there and return the solution. This solution will always be the shortest. However, because breadth-first-search scans every single child state at the current depth level, it could take a long time to search, especially if the tree is very wide (with lots of available actions per state).

Depth First Search

With depth-first-search, the initial state is evaluated and all child states are pushed onto a stack or queue. The AI then moves down the tree to the next child state, then the next child state, all the way down until either a goal is found, or no more child states exist. When it reaches a dead-end, it backtracks until another available child state is found. It repeats this until it gets back to the initial starting state, and then chooses the next child state to head down.

Although depth-first-search might not find the most optimal solution to a STRIPS artificial intelligence planning problem, it can be faster than breadth-first-search in some cases.

A* Search

The most intelligent of the searching techniques for solving a STRIPS PDDL artificial intelligence AI planning problem is to use A search. A is a heuristic search. This means it uses a formula or calculation to determine a cost for a particular state. A state that has a cost of 0 is our goal state. A state that has a very large value for cost would be very far from our goal state.

Similar to breadth-first and depth-first search, A search evaluates all valid actions for a state to determine the available child states. However, here is where it differs. Before selecting the next state, A assigns a cost to each one, based upon certain characteristics of the state. It then chooses the next lowest-cost state to move to, with the idea being that the lowest costing states are the ones most likely to result in the goal.

For example, an easy A* search cost heuristic is to use landmark-based heuristics for searching. In our Magic World example, we want to move from the town to the castle. We know that the character must visit the tunnel and the river in order to reach the castle. Therefore, we could assign a cost of 15 to all states by default. If the AI has visited the tunnel state, we reduce the cost by 5, resulting in a cost of 10 for this state. If the AI has visited the river, we again reduce the cost by 5, resulting in a cost of 5 for this state. Finally, when the AI reaches the castle, we reduce the cost to 0.

The code to implement an A* landmark-based heuristic might look something like this:

1 | function cost(state) { |

A* search usually provides the fastest way for finding a goal state in a STRIPS planning problem.

Getting Crazy with Magic World

Let’s beef-up our magic world domain, by adding a whole bunch of new actions. We’ll give our characters the ability to move, attack, open treasure chests, collect elements, and build a weapon. This will be more interesting! We’ll change our domain to be defined, as follows:

1 | (define (domain magic-world) |

In the above domain, we’ve defined a bunch of valid actions. A user or computer-controlled player can move from one area to the next, as long as that area is not currently guarded by a monster. If it is, the player will need to attack the monster first. Hence, we’ve defined an “attack” action as well.

We’ve also defined an “open” action to allow opening a treasure chest, and two types of treasures. We have an element of type fire and an element of type earth. Both can be collected for building a weapon. Once the player has both elements, he can build the “fireball” spell.

You can see how other types of spells and treasures can be added, by simply defining additional actions. Now, how about the problem?

Building a Fireball Weapon

Now, we’ll define an updated problem of figuring out how to build a fireball weapon in our world. The AI will have to figure out a plan for where to move, who to attack, and what to do, in order to build the weapon. We’ll define our problem, as follows:

1 | (define (problem fireball) |

In the above PDDL problem, we’ve added a lot to our world. We have a couple of monsters (an ogre and a dragon). Both monsters are guarding locations on the map. We’ve also added two treasure chests, containing magical elements that can be collected. A character will need both elements in order to build a fireball weapon. Let’s see how the AI STRIPS planner solves this.

Solution to the Fireball Weapon Problem

If we run the domain and problem, we get the following optimal solution.

1 | Solution found in 10 steps! |

The AI has successfully determined a plan, which involves moving from the town to the field, attacking the ogre at the river, and then moving to the river. It then attacks the dragon in the cave, and then opens the treasure chest in the river (the AI apparently wanted to attack the dragon before opening the treasure chest sitting at its feet - in reality, both actions had an equal depth cost, so the AI simply chose the first one that it found). It then collects the fire element from the treasure chest and moves to the cave. The AI opens the treasure chest in the cave, collects the earth element, and finally builds the fireball weapon.

What would happen if instead of using breadth-first-search, we try running this with depth-first-search? Let’s take a look.

1 | Solution found in 15 steps! |

Depth-first search produces a significantly longer set of steps to achieve the goal. It starts off the same as the optimal solution above, but at step 5, instead of opening the treasure in the river and collecting the fire element, the AI instead chooses to move into the cave and open the treasure there first. Interestingly, after opening the treasure in the cave, it then moves back to the river and opens the box there. This is effectively back-tracking. Once again, it repeats its steps of moving back into the cave to collect the element, and back to the river to collect the second element. Laughably, the AI then walks all the way back to town before building the fireball weapon!

This is a good example of the difference between breadth-first and depth-first search with STRIPS AI planning. The AI was simply following straight down a deep path of actions that lead to the goal state. Many other paths likely exist as well, including of course, the optimal path that was found by breadth-first search.

Integrating Automated Planning into Games and Applications

You can see how STRIPS artificial intelligence planning allows the computer to prepare a detailed step plan for achieving a goal. Now, how would you use this with a game?

In the main loop of a game, where the screen is continuously redrawn, there is usually associated logic for moving NPC characters and performing other necessary tasks at each tick. An automated planner can be integrated into this loop to continuously update plans for each NPC character, depending on their goals. Since a player or other NPC character can affect the state of the current world, we would need to update the plan at each tick, so that it reacts to any changes in the current state and updates its plan accordingly.

In this manner, the problem PDDL file could contain a dynamically updated :init section, where the current state of the world is described. The :goal section would remain static, while the :init section changes. At each defined interval, the AI would re-execute the automated planner to produce a new plan, given the state of the world. It would then redirect the NPC character to whichever action is next in the computed plan. The resulting plan may contain less or more action steps to achieve the goal. As the initial state of the problem PDDL changes, so too would the formulated solution plan.

Other Automated Planning Algorithms For Speed

It’s important to maintain search speed as a top priority. Since the automated planner may well be running at a frequently defined time interval, the faster the search can complete, the higher the application response rate. You’ll likely want to use an optimally programmed A* search heuristic.

For faster automated planner searching, you may even want to upgrade to other types of artificial intelligence planners, including GraphPlan and hierarchical task network (HTN) planners.

Trying an Automated Planner Yourself

You can experiment with different STRIPS PDDL domains and problems with the online application Strips-Fiddle. Try any of the example domains or create an account to design your own artificial intelligence planning domains and problems.

For integrating STRIPS-based AI planning into your application or game, you can use the node.js strips library, which supports breadth-first, depth-first, and A* searching. The homepage for the strips library provides some higher-level overview on the library, including an example of the Starcraft domain.

Domains and problems can be loaded from plain text files into the node.js strips library. Running a problem set can be done with the following code:

1 | var strips = require('strips'); |

By default, depth-first-search is used. You can change this to breadth-first-search by adding a boolean parameter to the solve() method, as follows:

1 | // Use breadth-first-search. |

You can also specify a cost heuristic to use A* search, as follows:

1 | // Use A* search to run the problem against the domain. |

For more details, see the Starcraft strips example. Give it a try and have fun!

About the Author

This article was written by Kory Becker, software developer and architect, skilled in a range of technologies, including web application development, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and data science.

Sponsor Me